By now we all have a good sense of what it’s like to be trapped at home indefinitely. Will we be allowed out by June? August? The year 2021? Or are we like a country full of tigers, doomed to live out our days in captivity?

As the days of quarantine and social isolation turn into weeks, then months, reality can start to feel like nothing exists outside of our four walls, outside of our own streets. Does the rest of the world even exist anymore?

In the case of Gemma (Imogen Poots) and Tom (Jesse Eisenberg), the answer is a solid NO. Vivarium (2019, Prime Video) was meant to be released theatrically in March, but thanks to everyone’s favorite virus it’s available to stream instead.

There’s not much to Gemma and Tom’s background info; they’re young, in love, and they’re looking to buy a house together (Awww). They’re like a nice, average, heteronormative couple full of so much optimism that they immediately trust a freaky real estate agent who works in an office that features nothing but identical houses. This agent takes them to a development called Yonder and shows them a move-in-ready house. By move-in-ready, I mean it already has a baby nursery painted blue (for a boy!), furniture, and clothes; well, t-shirts. The shady agent who is definitely not a weirdo leaves them without so much as a good-bye.

The game is on.

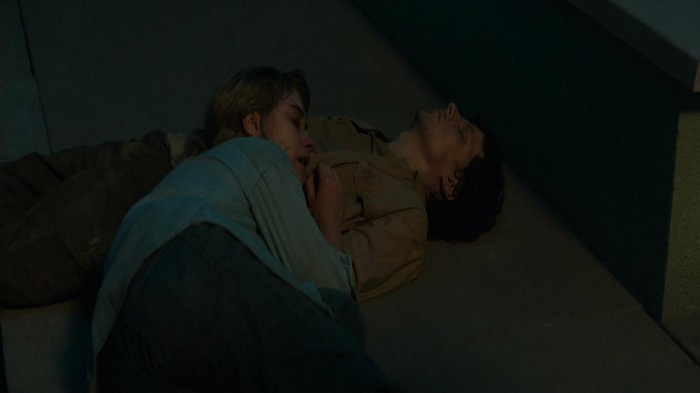

Gemma and Tom try to drive out of Yonder but can’t. Tom, figuring that Gemma’s lady-driving is what’s gotten them lost, takes the wheel until they run out of gas. Like all good modern horror movies, there’s no cell phone service, either. It looks like they have to spend the night at the house! The couple makes several more attempts to leave Yonder, failing to notice the perfectly shaped clouds that never move or the fact that no one else seems to live in any of the other Yonder homes. No matter what they do they wind up back at the same house, kind of like trying to leave a museum without going through the gift shop. Tom tries to burn down the house; it reappears with everything inside like new. The next morning there’s a package: it’s a baby! A boy! With no return label or Amazon drop-off location (Almost like that blue bedroom was done on purpose)! The child, who is never given a name, grows scarily quickly, looks eerily like the real estate agent, talks with a grown-up voice, and mimics everything Gemma and Tom say and do. Tom quickly grows tired of the kid and spends his infinite free time digging a hole in the front yard to escape the monotony of domestic life and possibly to try to find a way out, or a clue or anything helpful. Gemma isn’t a fan of the kid, either, but she at least makes a go of keeping him alive. By the end of the film, the child is a young adult, although only a few months have passed for Gemma and Tom, who now are sick, exhausted, and probably thinking that renting wasn’t so bad after all.

Without our current situation, Vivarium would seem like a nightmare scenario straight out of Black Mirror or something similar. Instead, it’s a prescient on-point commentary on how many of us feel in the spring of 2020: stuck in one place; no contact with neighbors or friends, raising children who drive us crazy because we can’t send them to school, can’t hire a babysitter, and can’t return-to-sender; we only have each other for company. So much sameness, day in and day out, with no light at the end of the tunnel. Trapped. Hopeless. Angry.

The futility of existence outside of raising a child comes into sharp focus in Vivarium. Who are Gemma and Tom anymore, if not this mystery kid’s ersatz parents? The child does what they do, he says what they say — much like real-life children — he screams when things don’t go his way, especially when Tom does Gemma’s “jobs,” like adding milk to the breakfast cereal. The child knows nothing of life save what he learns from his parents; or does he?

The child seems to know more of what’s going on than Gemma and Tom do, but all attempts to extract information from him wind up at a dead-end, much like Yonder itself. He watches strange shapes morph and move on TV. He mentions seeing another person outside the house, but won’t say who the person is.

As mentioned above, the child screams whenever Tom tries to do a “mom job,” that involves his care. And here’s where Vivarium gets interesting. While Gemma and Tom start the film like a modern, progressive couple who respect one another as fully-formed human beings (remember when Gemma was driving the car?), the stress and frustrations of their situation gradually nudge each of them into more traditional gender roles. Only Gemma is “allowed” to take care of the child, whether she wants to or not, despite her repeated reminders that she’s not his mother. Tom leaves the house every day to do manual labor, Gemma cooks and does laundry, and Tom becomes emotionally distant and even abusive. Vivarium is an uncomfortable and startling look at how easily progress devolves in the face of overwhelming stress.

Gemma and Tom start as a strong team, only to turn against each other as the days turn into weeks turn into months with no end in sight. Their protestations at the situation become weak and uninspired. Their will to live becomes drains their energy. This is their situation, even though they didn’t ask for it, didn’t want it, and apparently did nothing to deserve it. They’re stuck, and their only hope is to keep putting one forward in front of the other every day until they die. Even if this weren’t a bleak metaphor for the global quarantine, it’s certainly a metaphor for parenthood. Why else do we have children, if not to replace us someday? To live on long after we’ve served our usefulness?

The days of self-isolation and social distancing will end (probably, we hope), and right now that keeps us going. Even when the days drag, the kids scream, and the sameness threatens to bury us, we at least have some inkling that this will all be over. For Gemma and Tom, unfortunately, their situation ends only when their work as “parents” is done.

Movie Review originally published by Meredith Morgenstern on Medium

Comments