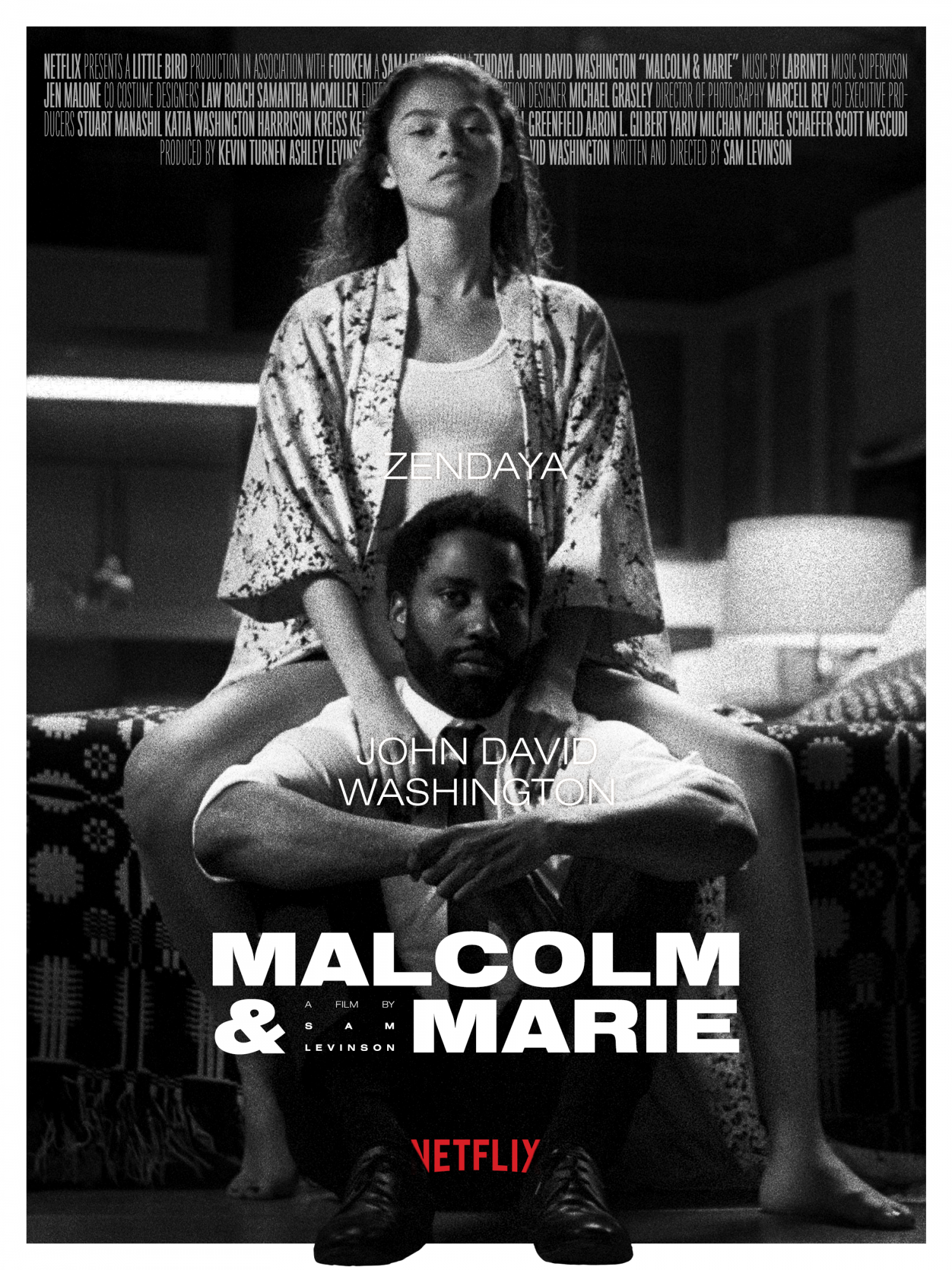

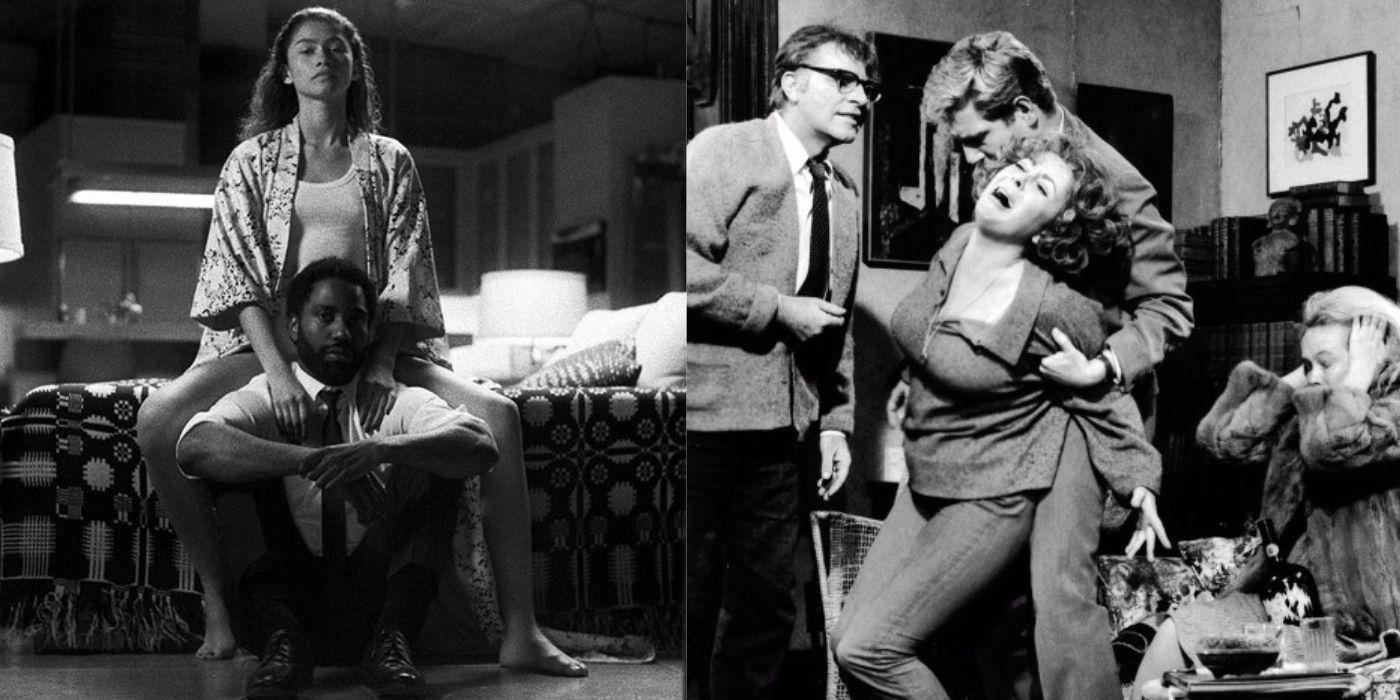

Let’s jump right in with why so many critics are calling this film an enormous flop. It has come to a common consensus that Malcolm & Marie is a shallow replication of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. If comparing the two, then yes, Malcolm & Marie is a pale replication of its predecessor. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf had more complexity in the plot, more mystery with the characters, and even more depth throughout the storyline. Malcolm & Marie throws in new conditions, new generations, and switches around the entire plot in order to center a black couple who criticizes the sole thing that they are involved with. Inadvertently it causes the question to rise: Which film is most authentic? Yes, the arguments get repetitive, but in the end they all lead back to one objective: a visual representation of a modern day power struggle.

Keeping in mind, both films are centered around a dysfunctional and abusive relationship, Martha (Elizabeth Taylor) and George (Richard Burton) in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf brought people into their drama. While that made for a great plot at the time, it isn’t something that is likely to happen in the 21st century–especially in the black community, no matter how wealthy one becomes. Second, Martha and George’s relationship was depicted as something normal that they do. Whether George is there because he truly love’s Martha or because he is simply “too numb to care anymore” it is clear that they have some sort of arrangement between them. Malcolm and Marie have no such thing.

Marie feels as if she is being victimized, and so she speaks out about it, or rather yells, and Malcolm disregards her attempts and desires on multiple occasions, even when she wished “to ask him a question without making her feel like shit.” The last thing that must be addressed is the circumstances. Not only are Martha and George a married white couple who have been together for years, they are in full sync with each other, older, and much more aware of themselves and the situation that they are in. Martha is conscious enough to know that she loves George, and he her–she just “doesn’t want it.” Malcolm and Marie aren’t married after being together for years with loads of baggage between them, but Malcolm blames any wrong doing and self sabotaging on Marie, rather than taking responsibility for his own actions and reactions.

Them not being married feeds into the ongoing stigmas and stereotypes of a dividing black community. Whether this was intentional or not, now it seems as if becoming a “good girlfriend” is the goal, rather than becoming a wife. Black women are not on the same page with their men as white women are with theirs, and it is yet again shown on screen by even comparing these two films to one another. Do they have similar styles? Yes. Similar plots? Maybe. But a film cannot compete when is doesn’t even compare. This film deserves recognition for its psychological approach to human nature as well its merits in its own rights.

Zendaya gives a phenomenal performance as Marie. Should we expect anything less from the Euphoria star? She played a women who has heard the same thing time and time again, living the same “empty” life day after day, and played the same supporting girlfriend role over and over again. Nothing Malcolm (John David Washington) said surprised her. As soon as Malcolm said his first words in the film Marie opened the door and went outside to light a cigarette, already annoyed. She does this throughout the film every time Malcolm says or does something inconsiderate of her feelings. Others said her performance was bland and non-authentic, but I disagree. A smart women knows that silence is power, especially when dealing with a narcissist like Malcolm.

Unfortunately, she was not able to keep that power because she fell victim to her own emotions, every great women’s downfall. She responded by telling her lover, “Nothing productive is going to be said tonight,” and it wasn’t. He verbally attacks her while she sits on the bed, doing nothing, saying nothing–then again while she’s in the bathtub, doing nothing, saying nothing. She just takes it. Almost like she likes it, an observation which Malcolm mentions later on during a heated argument.

Malcolm, on the other hand, started goading her from the beginning. First it started small, saying things like, “you don’t work in film,” knowing she was an actress. The it goes to telling her to, “shut the fuck up,” when she asks him to leave the room during the brink of their second fight. David Washington’s character is one track minded and enjoys either resistance or not getting what he wants. Stemming from his work life’s complaints to his issues with his girlfriend, he seemingly has no remorse or is in extreme denial about who he truly is and what he shows the world. Even when he tells Marie that he loves her during the bathtub scene, he is condescending and still spewing all her faults. He is a walking contradiction, a perfect example of a narcissist. Marie figures it out during the film and tells him. Every-time he isn’t tearing Marie down, or hyping himself up about his accomplishments or what he did for her, he is telling her how she is and what she can or can’t do, while saying he doesn’t want to control her. Confusing, isn’t it?

The complexity of his character is marvelously well written. What I didn’t understand was why he was out of breath every-time he gave a long monologue–he doesn’t smoke or have asthma in the film, so that part was unclear and seemingly unnecessary. Yet, Marie never used it as leverage while arguing with him, even though he dug beneath the belt and brought up her trying to kill herself using a pair of nail scissors and other harsh things.

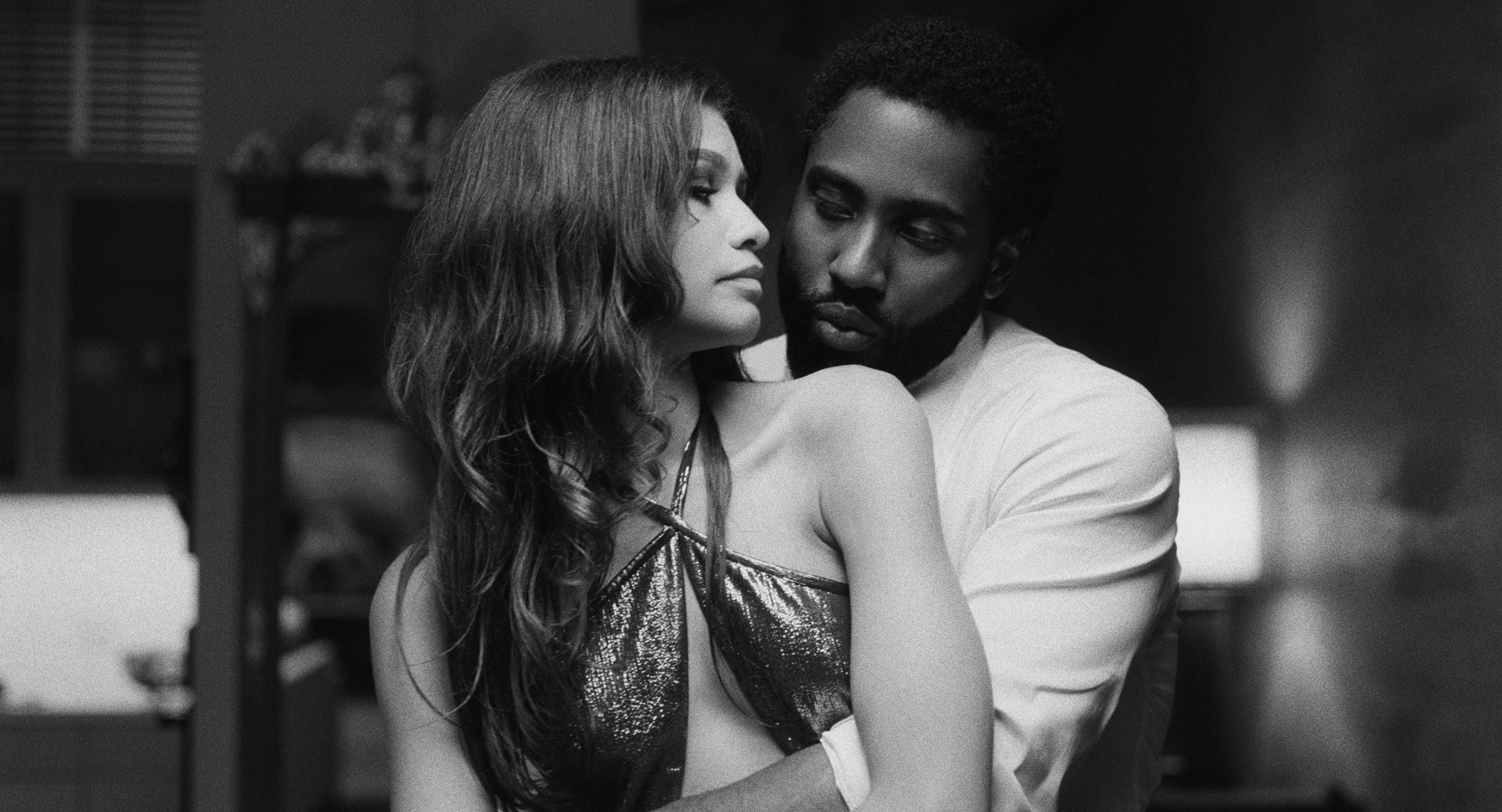

Together the pair are like sharks. Circling, calm, circling until one lashes out and draws blood. The other seemingly waits, thinks, and then is forced to respond in order to get that power back, to soothe their own egos. Then the cycle repeats–human nature at its finest. They both say things out of built up emotion and hidden truths, while Malcolm doesn’t have the introspection think that maybe he’s going too far and to possibly stop while Marie doesn’t have the introspection to truly value herself. How can Malcolm expect to value Marie if she doesn’t even hold herself as if she’s valuable? They’re two split peas in one broken pod. The complexity and depth of these two characters represent two halves of a whole coming together to form a relationship. As you can see, they form a dysfunctional one that doesn’t work long term…it reenforces the idea that in order to have a functional relationship one must be whole on their own and cleanse themselves of their baggage first.

While it seemed like this film’s protagonist is Malcolm, can we take a second to contemplate that, as Marie pointed out, “without her living her life, there would be no film.” Take that as you will, but Malcolm not only obsesses about his girlfriend whenever she is away for a few seconds–he literally would not have became who he was without her. She is not only defined as his girlfriend, who he loves, but depicted as his greatest muse. Marie knows that, and so does Malcolm. Contrary to what he accuses Marie of doing, he is the one who has a big ego (he flauts it multiple times during the film) and he is the main one projecting his feelings onto her the entire film. Not to mention Malcolm was with Marie when she was barley out of her teens. She was a naive, “drugged out” girl before she met him, and he essentially “saved” her. That has already created a hero complex on his end and a damsel in distress on hers. All roads lead back to Marie. Is it not a possibility that Marie, or in this case, her life, is who or what the story is really about?

On top of the phenomenal acting, and great dialogue between the two characters, the cinematography was ravishing! The sound was outstanding! The production design was simple, yet intrinsic. The minimalistic approach in the Malibu beach house represented how little they really have going on in their relationship. The storyline may have been much simpler than “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf,” but all the more insightful, and much more animalistic at its core.

Comments