In My Octopus Teacher, documentary filmmaker Craig Foster models healthy masculinity by showing us a trusting, gentle, and emotionally fulfilling bond with an octopus.

While it is important to talk about toxic masculinity, examining the inverse—healthy masculinity—is also crucial. Often, films give us realistic examples of harmful masculinity—depicting men who use their strength to harm others or who become overprotective and possessive. These films can teach important lessons about negative behaviors to unlearn and avoid. Films that portray healthy masculinity are equally crucial—they present positive models of masculinity for viewers to follow. (It is important to avoid the assumption that masculinity = men because not all men pursue masculinity as a goal and plenty of non-men embrace masculinity.)

Healthy Strength

Masculinity is often tied to the concept of strength, which in turn can be harmful or healthy. Often, when imagining strength in the context of the natural world, we think of destructive, cliché images like explorers slashing their way through jungles with machetes or strong muscles hacking down trees for firewood. What Craig Foster accomplishes in My Octopus Teacher requires immense strength, but of the opposite, constructive kind. To navigate underwater, Foster must strengthen his body to become a stronger swimmer and strengthen his lungs to hold his breath longer. He must also be strong in the way of endurance: to traverse the gorgeous undersea world and gain the trust of the small and inquisitive octopus, he must visit as often as is possible, typically once per day.

Gentleness and Knowledge

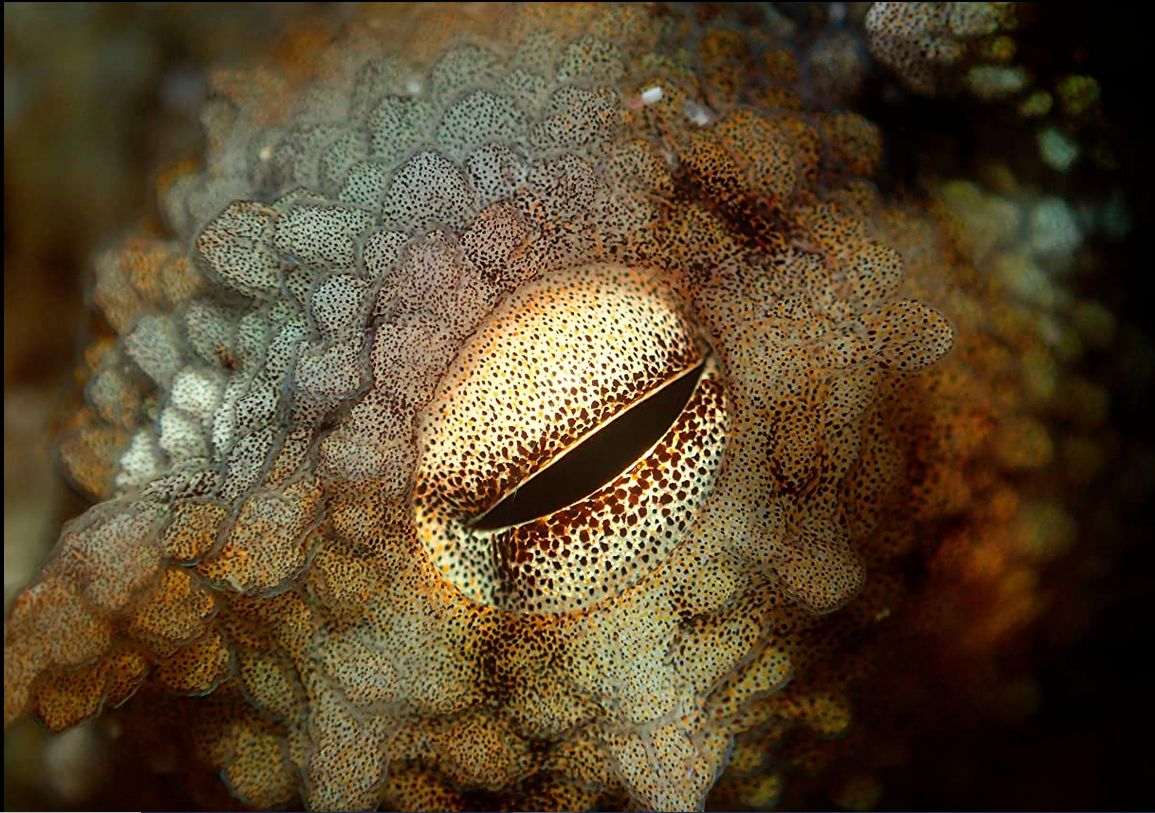

The octopus is a trickster both to elude predators and to entrap pray. To become close to an octopus, one must avoid any behavior that could be perceived as a threat. Above all, one must be gentle.

Often gentleness is often coded as feminine, and due to misogyny, it is thus often coded as inferior. Men are told to “man up” and to show less sympathy to animals or people who are more vulnerable. To gain the octopus’s trust, Foster must be careful, gentle, and unobtrusive, despite being tall and muscular. Foster is honest about the challenge: once, when he approached too fast, he almost doomed his experiment by scaring the octopus away. Only by careful research and tracking does he find the octopus again.

When the octopus does become trusting, she holds hands with Foster and nuzzles against him, similar to a snuggling dog or cat. These scenes are portrayed with gorgeous, calming music, and are truly stunning to observe. By being gentle, Foster experiences rare and incredible interactions. Because of his tenderness, he observes behaviors in the octopus that he can find no prior documentation for, like her ingenious strategies for overcoming predators. Gentleness can lead to greater scientific knowledge. Healthy masculinity, compassion, and tenderness are not hindrances but strengths.

Interference with Nature? Or Inescapable Interaction?

My Octopus Teacher contains some frightening scenes. While most of the film has gorgeous music and serene views of the ocean, sharks are an ever-present threat both in the environment and the documentary’s narrative. When the octopus is attacked by a shark, he worries that his presence could have somehow lead to the attack. He admits that due to this guilt, he fed her a meal while she convalesced. Although driven by a scientific mindset to not interfere, Foster was overcome by his care for the octopus. Rather than demonizing this display of emotion and portraying it as a bad thing that ruined an experiment, Foster acknowledges his emotions, doesn’t try to hide his interference, and concludes that his actions likely didn’t make a difference.

Later in the film, we find out the octopus has innovated a new hunting strategy using Foster. She traps a lobster between herself and the observing Foster, preventing her meal from escaping. This differs from many famous nature documentaries (like March of the Penguins, for example) that avoid showing humans onscreen and contain no human presence aside from a narrator. My Octopus Teacher emphasizes that we cannot be separated from our environment. We cannot disappear and be unnoticed. We are essential parts of our ecosystems, food chains, and interspecies neighborhoods.

Who is in Front of the Camera? Who is Behind It?

The human cast of this documentary is very small, focusing on documentary filmmaker Craig Foster and occasionally his young son Tom. Although the film’s human subjects are a man and a boy, the film is directed by Pippa Ehrlich and James Reed, and Indian environmental journalist Swati Thiagarajan, Foster’s wife, serves as the production manager. In her own words, Ehrlich explains, “… [Craig Foster] sent me the treatment. I remember I was sitting at my desk at work and just started crying. Something in the story just resonated with me on a level I didn’t really understand. At that point, despite the fact, we had no funding, we were going to be making the film in an attic, I quit my job.” Ehrlich’s belief in the film and willingness to sacrifice for it is the reason the project exists today. While ideally most films will have a diverse cast in front of the camera, a diverse team behind the camera is a key asset.

Still, I hope this film inspires Netflix to take a chance on other nature documentaries, focusing on more diverse human subjects. Who else on this planet has a fascinating and unexplored connection to another species? The citizens of Istanbul interviewed in Kedi about their deep connection to cats come to mind. I hope Netflix is encouraged by the success of this documentary and funds similar projects with diverse production teams and subjects. Foster shows us how connecting with an underwater realm can teach us so many things; what might other people with other unique connections to nature show us?

Now the Sad Part

I have probably read Sy Montgomery’s article Deep Intellect from Orion Magazine upwards of ten times. I love re-experiencing the narratives woven through the article, from the octopuses interacting with puzzle boxes to Montgomery meeting Athena the octopus and holding her tentacles. Montgomery ends the article discussing how Athena’s death moved her to tears. Of course, it is one thing to know that octopuses have rather short lifespans and another thing to witness it. Foster observes his octopus friend go through the final stages of her lifecycle in one of the most poignant segments of the film.

Foster is so clearly moved by watching the end of his friend’s life. This time, he does not interfere, which takes a lot of strength. He simply observes the end, an ode to a friend, respecting her own needs and the needs of her interconnected ecosystem. Foster shows how we can be connected with nature, emotionally observing and caring for other creatures while also allowing them to live autonomous lives. He could have taken her out of the ocean, out of the food chain, but this would disrespect this system of life he’s come to love and understand. By feeling emotions, acknowledging them, but not acting inappropriately on them, he models both healthy masculinity and healthy emotions.

Why is this so Important?

I often think about this moment. Once when I was tutoring a third-grade boy, he told me his father was going to kill and cook their backyard chickens because the chickens were growing too old to lay eggs. He told me he tried bargaining with his father, arguing that they could eat the chickens after they died. His fear that their deaths would come to pass and his deep sadness at the prospect showed his deep connection and affection for creatures of another species. I wish he could have seen this documentary, so he could see a grown man who loves nature beyond how it might be of use to him, who feels a deep moving connection to another, a much more vulnerable creature of another species. That boy deserves to know that these emotions, this empathy and care, aren’t weaknesses, but strengths. We all deserve to know this.

Comments