Directors Mona Achache and Patricia Tourancheau center women—the very demographic true crime is designed to appeal to.

Part serial killer investigation and part courtroom drama, the French documentary The Women and the Murderer sets itself apart from other true crime documentaries by only interviewing women. The women involved in the featured case are varied: they include the leader of the crime brigade at the time of the killings (Martine Monteil), lawyers for the prosecution (Solange Doumic) and the defense (Frédérique Pons), and a mother (Anne Gautier) of one of the serial killer’s victims. This approach showcases the role of women in bringing down Guy Georges and gives women a voice after he silenced so many. The decision to center women is especially intriguing given the genre’s popularity with women.

True crime, like any genre, has positive and negative elements. Like any of women’s guilty pleasures, social guardians tend to pick it apart, despite men being allowed to enjoy similarly fraught media without constant demands of introspection. Women’s “guilty pleasures” from soap operas to Barbie movies are often neglected by critics, while media beloved by white teenage boys in the 80s receives blockbuster adaptations. (Admittedly, I absolutely love blockbusters.) So rather than celebrate or condemn, my goal here is to discuss the good and bad of the genre and examine where The Women and the Murderer fits in.

The Positives of True Crime

The Women and the Murderer opens with a montage of home video footage showing women enjoying themselves. Out with friends, partying, laughing and having fun, these women are easy to relate to. Then the music grows sinister, and the fun footage is spliced together with violent paintings and crime scene documents. The true crime genre appeals to women because it centers us. Young girls are raised to be vigilant: we are taught to attend parties in groups, watch our drinks, and never get so caught up in a good time that we risk our safety. It is no surprise true crime appeals to women: it centers our fears, our anxieties, and our experiences. The horror genre functions in similar ways.

In crime films, women often feature as violent perpetrators or tragic victims. The Women and the Murderer gives us a much wider range: the women interviewed are mainly professionals, which feels notable given that Guy George targeted professional women. The choice to center female voices never feels like a gimmick: these are the people who investigated the crimes, attended the trial, and secured the conviction. They are undoubtedly excellent sources of information. Still, the decision to only interview women means that all of the subjects are white French women. In a genre that already centers white women, this approach had the potential to leave important voices out. Any documentary filmmakers interested in taking a similar approach of centering women would really need to consider whether they are omitting crucial voices of men of color or voices of trans or non-binary people.

Where True Crime Can Go Wrong

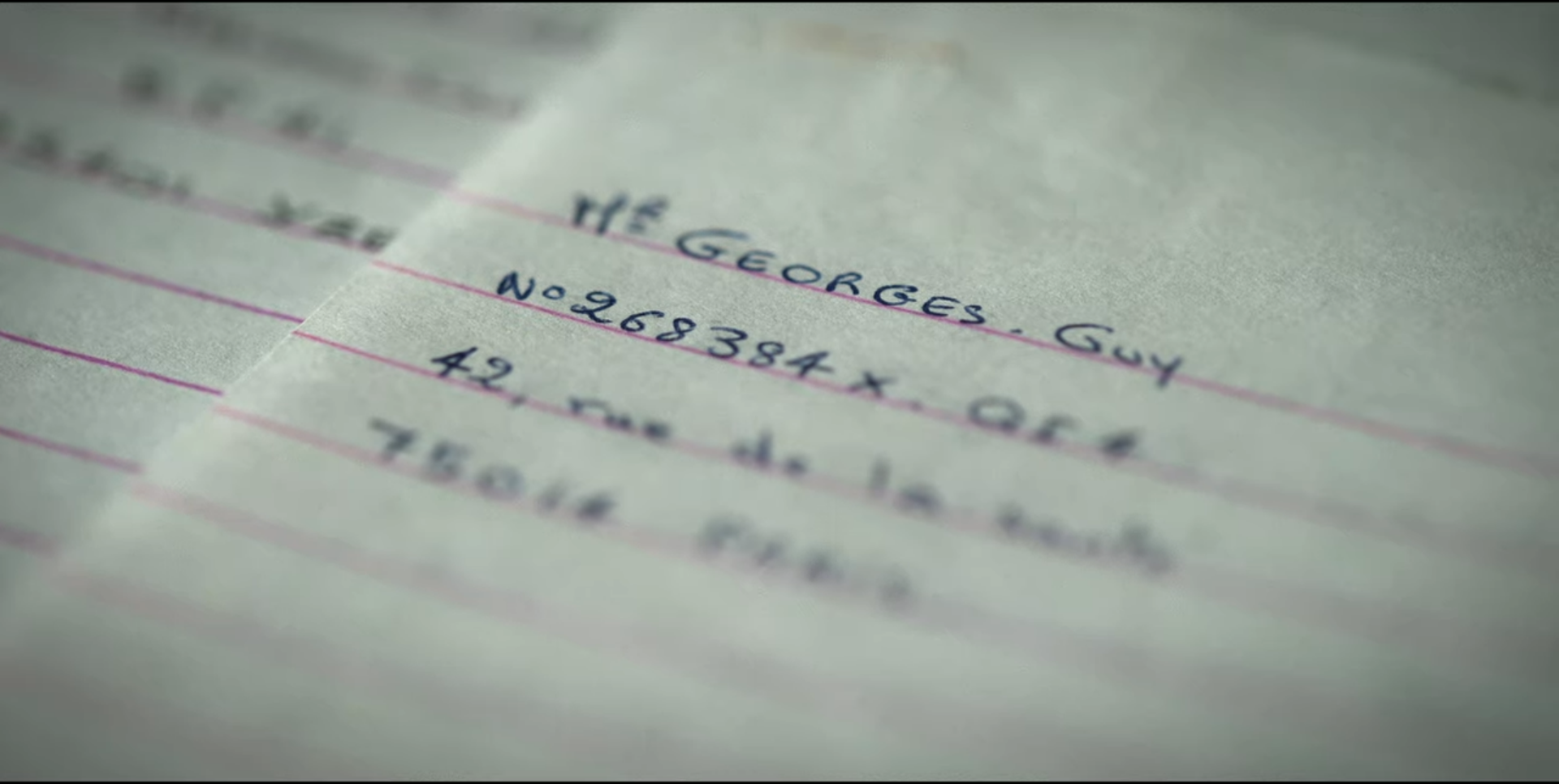

True crime at its worst is exploitative and sensationalist, showing little respect or regard for victims. One way The Women and the Murderer avoids this is by not including salacious, over-dramatic re-enactments. The crime scenes are recreated through black and white photos, maps, and illustrations. This approach remains respectful while also conveying necessary information. During the second part of the film, we see a fascinating sort of re-enactment. Solange Doumic re-enacts a conversation with Guy Georges by approaching the place where he sat and reciting the conversation she had with him. The resulting scene is an incredible illustration of one of the most important moments of the trial, and since Doumic speaks for both herself and Georges, her voice remains central.

Another issue of true crime can be its implication that the justice system is always just, DNA evidence is correct and infallible, police always solve crimes fairly and honestly, and crime must be approached as though criminals are irredeemable and evil. Luckily, The Women and the Murderer avoids falling into these pitfalls.

For one thing, Guy Georges’s childhood is portrayed as tragic, and various interviewees express sadness when reflecting upon his abandonment. As horrific as his crimes were, this attempt to understand is important. Often, white men who kill, even some of the most gruesome and horrific serial killers, are given tons of screen time and attention to understand their minds and motives, while black men who kill are denied this introspection. The ending of the film explores Anne Gautier’s decision to write to Guy Georges and her hopes that his letters might be studied and used to prevent future potential killers from committing crimes.

The Women and the Murderer doesn’t hesitate to offer multiple perspectives. Martine Monteil is given space to speak about how important it was for her to solve the crime and shares her perspective of how hard her department worked, while Anne Gautier expresses frustration that police failed to interview some of her daughter’s neighbors. The police’s failure to catch the killer before he commits more crimes and their decision to use DNA despite it going against official protocol is also mentioned. The court trial lets us see that the investigation used evidence in addition to the DNA, which counters the dangerous assumption that DNA alone is enough to solve a crime. The Women and the Murderer stands out from other true crime media that focuses only on apprehending the suspect by devoting half the film to the courtroom trial. The documentary shows the importance of ensuring rather than assuming a suspect’s guilt.

Ultimately, The Women and the Murderer is a worthwhile addition to the true crime genre. My hope is that this will encourage more true crime projects to center women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people as interview subjects.

Comments