Bong Joon Ho’s masterpiece, Parasite (2019) became one of the few international films to break into the American mainstream. It received rave reviews from critics, earned 53 million dollars in the United States, and went on to win 4 Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Film. It is also the first international film to ever win Best Picture.

There are very few international films that transcend the niche groups of cinephiles who appreciate foreign cinema, and are embraced by the general American audience. With Parasite now on Hulu, I showed it to my sister: someone who is self-professed to not like movies. My sister came away saying she loved it and was completely invested in it. For someone who has never seen a foreign language film, she said it may as well have been in English, as she was so immersed in it that she forgot she was even reading subtitles.

Why does Parasite resonate with American audiences? What is it about this film that captures people’s interests? It may be the twists and turns it takes, not only changing drastically in the narrative but also in tone. It may be the conflicting feelings you have for the family; recognizing their actions are horrible but secretly hoping they get away with it. It may be that it is simply a really good movie, and one that a lot of people simply enjoy. However, I think it’s more than that.

There’s a special connection American audiences have with Parasite. While taking place in a foreign country, it is still very relatable. It speaks to our societal structure. It speaks to the gap between the lower and upper classes. It speaks to all of our inner desires for wealth and respect. Parasite speaks to the realities of a Capitalistic society, and Americans know full well what life is like under Capitalism.

Capitalism pits different classes of people against each other. The work of the lower class feeds the profits of the upper class, and the profits of the upper class feed the lower class. It’s a system that requires co-dependency, not unlike a parasite and its host. What question Parasite poses is, “who is the parasite and who is the host?” In a capitalistic society, the gap between classes ensures that one class of people live with constant overabundance, while the other class of people live with constant scarcity.

With a fixed amount of money, unequally distributed, this guarantees that there will always be those who have too much and there will always be those who have too little. Those who have too little will always want to become one of those who have too much, and those who have too much will always be terrified of becoming one of those who have too little. Parasite follows a lower class family that deceives their way into the upper class before they fly too close to the sun.

Parasite first establishes the barriers between the two classes. Bong Joon Ho does this visually by continuously staging lines or physical barriers between the characters, separating them by class. This effect is also done largely by Dong Ik (Sun-kyun Lee), who repeats many times that he doesn’t want the driver “crossing the line”. Essentially, he’s okay with those in the lower class feeding him, cleaning for him, driving him — doing everything for him — as long as the help remembers to stay on their side. This is demonstrated with the motif of these privileged characters smelling Ki Taek (Kang-ho Sang). Dong Ik says at one point that the stench crosses the line, this being the stench of his poverty; Ki Taek can’t afford to keep his clothes clean.

In the third act of the film when Yeon Kyo (Yeo-jeong Jo) smells Ki Taek in the car, Ki Taek has literally been covered in sewage water, unable to shower, and is barely able to find clean clothes. The smell is a reminder that Ki Taek is not one of them. Throughout the film, as much as the family tries to integrate themselves into the culture of this upper-class family, they are continuously reminded that they are not one of them.

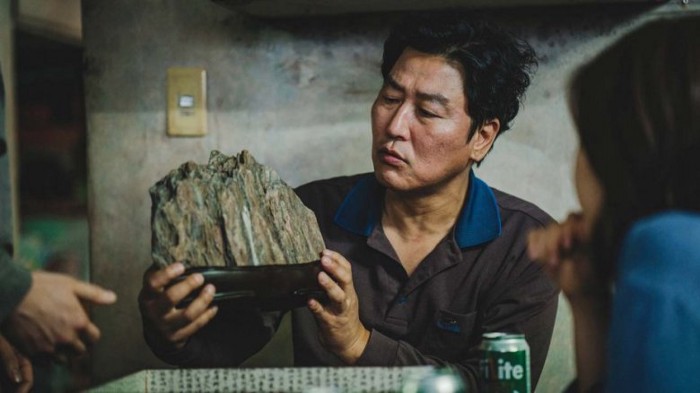

With the barriers in place, Ki Woo (Woo-sik Choi) wants to transcend them; he wants to be part of the upper class. Ki Woo talks about marrying Da Hye (Ji-so Jung), but that becomes problematic for him. At the beginning of the film, Ki Woo’s friend Min (Seo-joon Park) gives the family a big rock that is supposed to bring about wealth. When the sewage water floods their basement apartment, Ki Woo goes to save it. Upon finding it, however, he sees that it is floating in the water, revealing it to be hollow.

Later, when asked why he is still holding onto the rock, Ki Woo says that he isn’t clinging to it, but rather “it is clinging to me”. The pursuit of wealth is hollow, and the life Ki Woo desires so much isn’t what he thinks it is. Despite now recognizing this, Ki Woo still wants it. During the party, before things go south, Ki Woo asks Da Hye if he fits in with the party attendees; he still wants to be one of them.

After the sewage scene, Ki Woo asks his father what his plan was, to which Ki Taek responds that he has no plan.

“You know what kind of plan never fails? No plan. No plan at all. You know why? Because life cannot be planned.”

This may seem like a throw-away line, but it becomes crucial by the end of the film. After killing Dong Ik, Ki Taek is hiding in the basement. He uses morse code with the hopes that maybe his son will see it. That’s when the film launches into Ki Woo’s elaborate plan to free his father; he’ll become incredibly wealthy, buy the house, and then his father can simply walk up the stairs and join the family.

This is Ki Woo’s plan, a plan that is merely a pipedream that will never come to fruition. The point is that as much and as actively as Ki Woo wishes to become wealthy and join the upper class, it’s an unobtainable dream. As Ki Taek alludes to in the earlier scene, plans fail because you cannot plan for life. Ki Woo’s denial of the hollowness of his pursuit of wealth and his refusal to accept that he can’t control life persists to the very end of the film. This will ultimately lead to the death of Ki Taek locked away in the basement, waiting for his son to save him.

While Parasite acts as a social commentary for South Korean culture, it also speaks so directly to the issues that exist in American society. The middle class is shrinking exponentially. The upper class grows more and more wealthy, and the lower class are left with less and less. Parasite speaks to the co-dependency between these classes, and how both would be devastated by the absence of the other.

It speaks to how our society is structured so that the pursuit of wealth is the ultimate goal, and having as much wealth and power as possible is the game. Even when Ki Woo learns that this pursuit is ultimately hollow, in that the game is rigged against him from the very start so that he will never be able to reach the final destination, he still pursues it.

American audiences are seeing Parasite and are noticing similarities to their own lives. Audiences are recognizing their hopes and desires and realizing their frustrations. It’s pointing out to people the structural flaws in Capitalism, and the myth of the American Dream that anyone can ascend from rags to riches. The most brilliant part about this is that it’s all being done by a film set in South Korea, made by South Koreans.

Bong Joon Ho crafted a masterful film that speaks to so many different people across so many different parts of the world. It’s a thrilling movie with great moments of levity and horror, but it also makes us think. Even with all of the praise and acclaim it has received upon its release, I think Parasite is one we will still be discussing in the years to come.

Author: Nathanael Molnár, originally published [4/20/2020]

Comments