Taika Waititi writes, directs and co-stars in Boy, set in 1984 New Zealand. The film opens with Boy giving a school presentation under the title “Who am I?” The rest of the movie explores this universal question, which is the beauty of the film. It is very specific to this group of families in Waihau Bay during this very specific time, but completely relatable and familiar to everyone.

Many people were introduced to Taika Waititi after he dominated award season for JoJo Rabbit. His acceptance speeches included some of the most honest lines ever uttered to Hollywood. For example:

- 2020 BAFTAs: “I come from the colonies… and it’s very nice to take a bit of your gold back home where it belongs.”

- 2020 Hollywood Critics Association: “…the big dream is to slowly take away roles from white people”

- 2020 Academy Awards: “We are the original storytellers.”

This film does just what Waititi dreamed of — it gave a great coming-of-age story to Māori people without making a story of the Māori people as an exotic other. Boy is the story of a tween growing up, figuring out his relationship with his father, and the characters happen to be Māori.

Translations

Because I have small children, I watched this movie on Amazon Prime after my kids went to sleep. Out of fear of waking them up, I kept the volume low and took advantage of closed captioning. The Māori language is used here and there in the dialogue (very seamlessly), and oddly, the closed captions did not include the Māori word or the translation — it simply said “[foreign word]”. I am not sure if this is because the Māori language is not as regularly spoken as it once was, so perhaps the Amazon algorithm has not been set up to translate it. Whatever the reason, it is interesting that Waititi did not include translations/subtitles to the words either, making the Māori words only defined to non-speakers through context, yet not at all distracting.

During one conversation between Boy and Alamein (his father), they brainstormed a replacement name for “Dad” as it made Alamein uncomfortable. Ever living in a fantasy, Alamein suggests “Shogun”. Not understanding what Shogun was, Boy clarifies saying, “Like a ariki.” The father quickly corrects him stating, “Yeah, but he’s a samurai. Samurais are better.” Ariki is a Polynesian king or chief, but Alamein does not want that. He wants to be someone else — a character, not associated with his own cultural history. This distancing from his own culture comes across as immature and dense.

Fatherhood

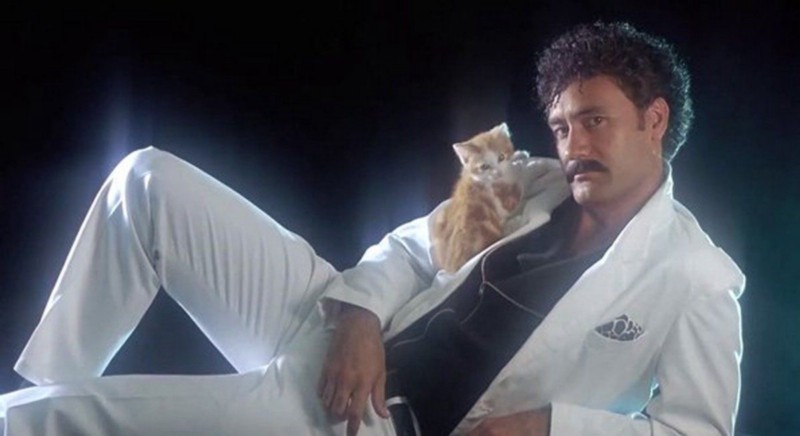

A big part of growing up is when your parents move from myth to reality. This is both disappointing and liberating for kids. It signals the beginning of adolescence, and growing up. Adults don’t know what they are doing all the time, and some adults themselves never move from fantasy to reality. Alamein is a perfect example of this. He is pretending to be as many things as Boy has imagined for him. He plays war, he plays gang-leader….he even plays a cool, smart road warrior. None of which he actually is. He is bumbling around trying to keep up this imaginary identity while making completely self-centered decisions. Even when Alamein attempts to apologize to Boy for embarrassing him in front of his entire community, Alamein explains that he is simply The Hulk. He never admits he made a bad decision — he just has anger that he cannot control like a fictional superhero.

All kids go through this realization, and everyone knows (at least) one adult who is stuck in a fantasy adolescence. I was so happy to see that there is no white savior for these kids. I worried at one point that it would be the white teacher who tells Boy he has potential, but thankfully the teacher is just an exposition character that adds a moment of humor. Really, there is no savior at all. The kids are raising themselves and saving themselves. This happens all the time to all kinds of children.

The Females

The closest thing to a savior figure would be the consistency of the women. Boy has only a handful of female characters: the memory of Boy’s mother, his aunt, his friend, Dynasty, his crush, Chardonnay, and his grandmother, Nanny. All of the women are almost mute in this movie — very few words are uttered by the female characters. The most dialogue comes from his aunt in only one scene, which is also the only scene when an adult protects Boy.

However, all of the female characters give the most loving energy to Boy through looks and smiles. These gestures are so slight and intimate, you can feel the love through the screen. The females in Boy’s life are not portrayed negatively at all. They are the strong ones, the helpful ones, the kind ones (perhaps with the exception of Chardonnay, only because we don’t really know her at all). The women hold everything and everyone together. They don’t need to participate in the crazy fantasies of their male counterparts. They do what they have to do: work hard and make mature, responsible decisions, all the while observing the ridiculous image that the males try to create.

Pop Culture

Boy is overrun with pop culture references, most included for comedic affect. The most notable is the constant reference to Michael Jackson and his album, Thriller. Despite whatever your current view of Jackson may be, in 1984, he was a god and Thriller was the most exciting thing in the world. Also, because it is 1984, no one really had access to information about Michael Jackson like we would now. He was a legend creating the best music that this generation had ever heard. Michael Jackson was the coolest. When Boy imagines Alamein as Jackson, he has just set the barometer of cool as high as possible, and considers his dad to be right up there. In his absence from the kids’ lives, he was built so high that it was a long and heart-wrenching fall.

Like his sons, Alamein seems obsessed with pop culture knowledge as status. He tries to discuss the film, E.T. several times, along with Shogun, the A-Team and The Incredible Hulk. These references remind the audience that these characters live in a different world, while allowing Alamein to showcase how knowledgeable he is about all things cool. Another attempt to stay in a fantasy, rather than face (or god-forbid discuss) reality. We all use movies, books and television shows to escape reality, especially right now. It can be good for one’s mental health to be distracted. The difference is that most of us know how to switch back from it — Alamein remains there. Boy was waiting for his father to return and save him, or at least guide and teach him. Alamein is incapable of this and as soon as Boy realizes that he is more aware of the destruction produced by fantasies, he can appreciate his real life.

Conclusion

The end credits show all of the characters dancing and lip-syncing to a mashup of the haka and Thriller. The dancing is a beautiful symbol of their own culture with the adored pop culture. It is my favorite scene in the film, and possibly the best credit sequence I have ever seen. If nothing else, watch the film to see this. Every viewer can relate to Boy and/or Alamein, perhaps Dynasty or Rocky as well. Boy is a well-made, fun and touching story with amazing Māori characters.

Written by Sarah Erskine

Comments