The History and Lessons behind Norma Rae

In 1979, the film Norma Rae shared the story of how the titular woman rose up for her fellow workers. Based on a true story, inspiring and relevant today, showing how films can teach something relevant about the world itself. This article will begin by going over the historical events that inspired the film, the film’s production, theories about the film, selected literature reviews, and my own personal thoughts about the film and true story behind it.

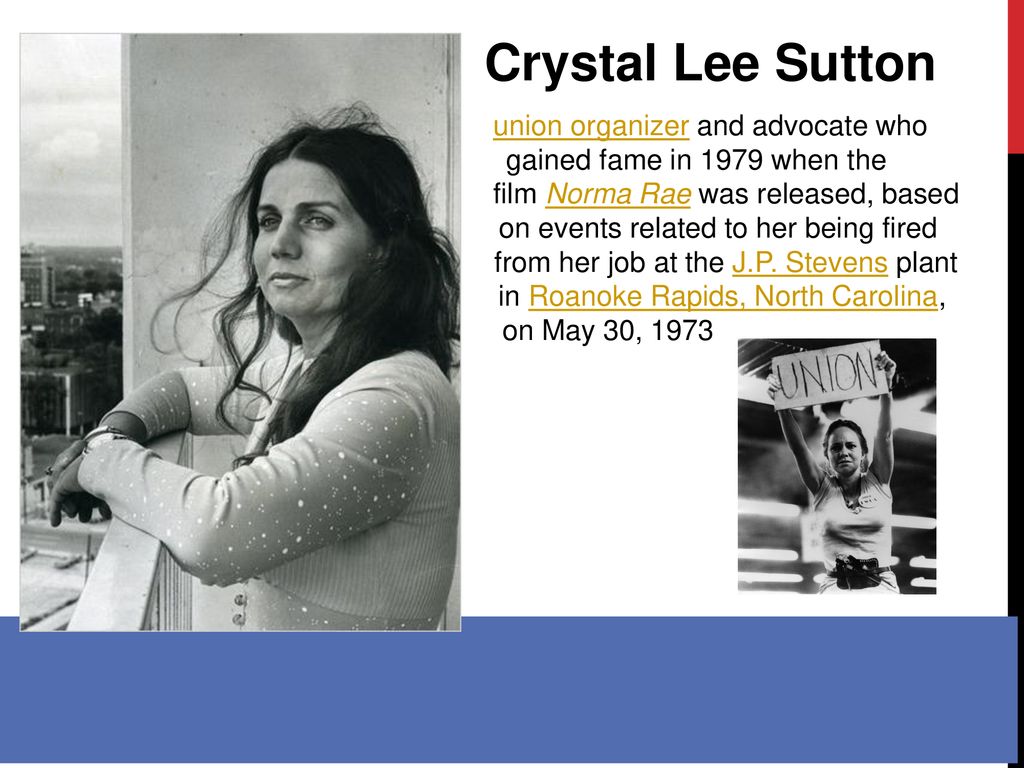

Crystal Lee’s Origin

In the early 1970’s, there was a woman by the name of Crystal Lee. She worked in the J.P. Stevens Cotton Mill in her hometown, Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, where she folded towels and prepared gift boxes. She and the other workers would make about $2 an hour. She could be considered one of the lucky ones, since she was away from the weaving area of the factory, an incredibly hot, humid, loud, and dangerous environment (Toplin 217).

The owners of the factory cared little for the well-being of their workers compared to production. The mistreatment of workers is further evidenced by the lack of windows in the factory, the company’s insistence on keeping the temperature of the factories at eighty degrees, and humidity at sixty-five percent, in order to achieve the best possible weaving despite the adverse health outcomes of the workers. Some workers even lost limbs to machines. The windowless environment resulted in psychological damage to the workers. Many workers experienced hearing loss, including Lee’s mother, and even death due to either heat stroke or brown lung disease caused by cotton particles in the air (Rein, 1979).

This factory was in dire need of the eventual workers’ union to show up and give these underpaid and suffering people a fighting chance.

A lot of these over worked and underpaid workers gained a glimmer of hope in the form of Eli Zivkovich. He was visiting the small town in order to have the J.P. Stevens Cotton Mill join Zivkovich’s workers’ union. Zivkovich first started by trying to speak with the managers, looking to post on their bulletin board, neither of which the company made easy for him. Lee herself was uninterested in the union until the J.P. Stevens Company sent her a manipulative apology letter, hoping to persuade her that things would get better. They were attempting to dissuade her from joining the union, which backfired, since she did not trust the company. Lee sees the notice of a union meeting posted on the factory’s bulletin board, triggering memories of the union her ex-husband joined when he worked at the paper plant and all the benefits he received (Toplin, pp. 218). This is coupled with her bad experiences with unions during her school years and her father telling her that the only thing unions were good for was creating trouble. She ultimately attends Zivkovich’s meeting.

“When she [Crystal Lee] arrived at the meeting, she discovered that there were only four or five [W]hite [people] present, along with about seventy [B]lack [people] (Toplin 218).” This is partly because the meeting was held in an African American Church. The church’s ministers supported the union cause, referring to the need for unions in their sermons. African Americans were angry about the privileges that the White workers had in the factory, such as being more likely to receive promotions or be hired in the first place. In contrast, only one third of the workers present in the mill were Black (Toplin 219). The union would pave the way for peace and equality between Blacks and Whites by giving them a common cause. These racial dynamics could only be touched upon briefly in the film in order for it to keep the focus on Norma Rae’s journey. However, these events present in the true story of Crystal Lee demonstrate that the union can do more good than harm, contrary to her father’s sentiments. The workers’ union even had the potential to help end some of the segregation present in the factory and, potentially, in the town.

Beyond racial segregation, the town also had a problem of being segregated by class as well. The upper class citizens didn’t need to work in the cotton mills, unlike the working class, limiting their empathy. This also resulted in the upper class citizens mocking them on a daily basis, such as calling them cotton heads (Toplin 220). The movie presents the union as a chance for the working class to raise their quality of life. This further motivates Crystal Lee to trust the union.

During the meeting, Lee hears an inspiring speech given by Zivkovich, addressing workers’ concerns and why his union is a potential solution. “The day after the meeting, Crystal Lee appeared in the mill proudly wearing a union button (Toplin 219)”, something her employers didn’t like. After seeing this, the mill did everything it could in order to keep the union out of its business. One such method was even threatening to worsen work place segregation. They threatened to separate the White and Black mill workers, going so far as to manipulate the White employees into thinking that Black employees would “control” the working environment if the factory did integrate with the union. The implication being that they would definitely make the conditions worse for the White workers, but give themselves all the benefits, in retaliation for years of mistreatment. They spread these rumors in order to cause discord within the union, keep communication between the union members to a minimum, and to maintain White people as the dominant race within the town and factory (Toplin 220).

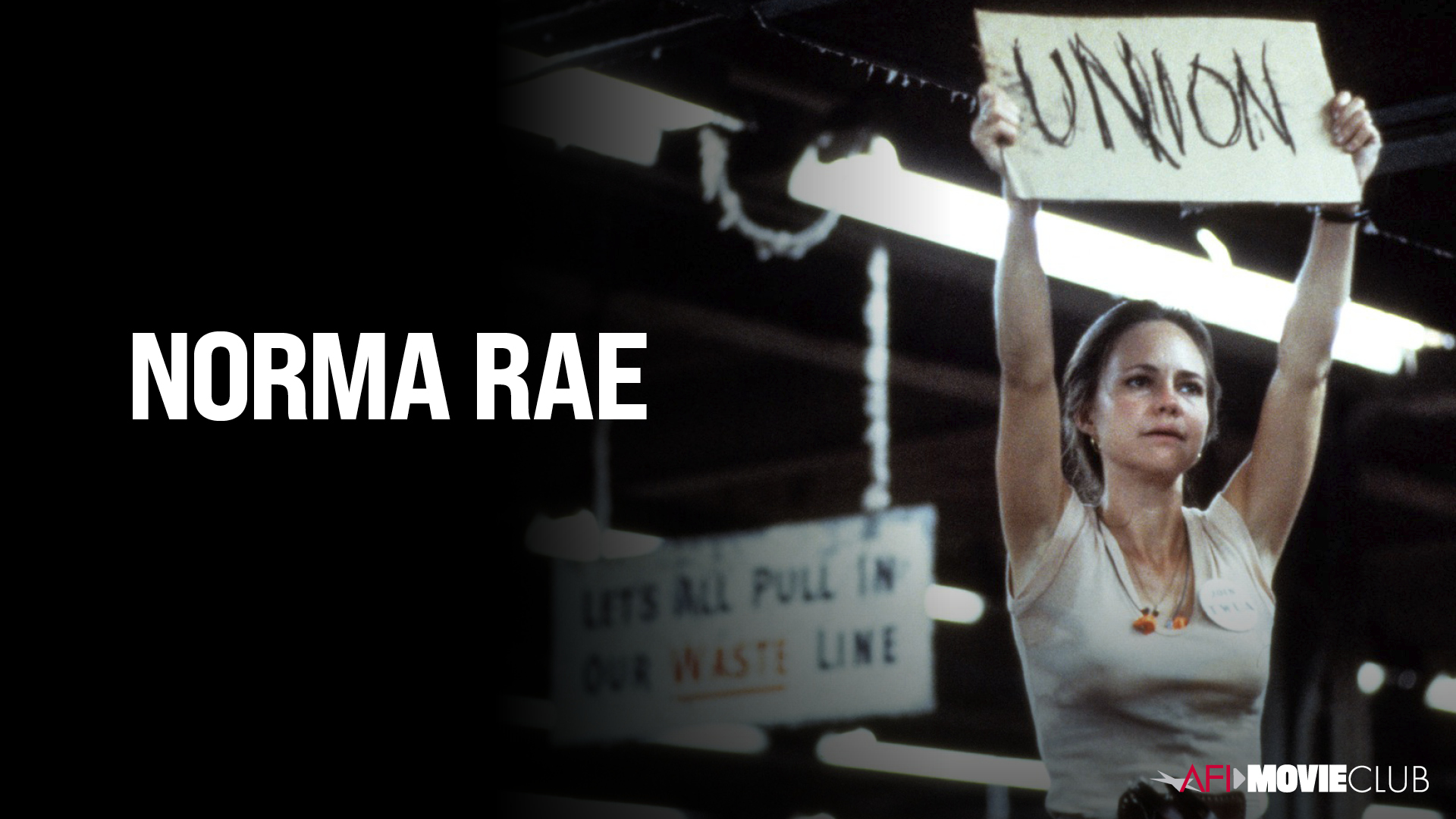

They tried promoting Lee in the plant in order to monitor her, further creating tension between her and the other union supporters. They promoted her, knowing that she was an inspirational figure to the union, and that this pressure and promotion would cause her to quit the union. Even with this new promotion, Lee stuck to her morals and continued her work in integrating the union. Lee even turned the tables on the company by reporting the company’s anti-union practices back to Zivkovich. This is where the climax of the film was inspired. Lee’s managers catch her documenting the factory’s latest change concerning wages at her workstation, and fire her. They told her to leave, but she wouldn’t. She instead stood up on one of the tables and held up a cardboard sign that read “UNION.” The other workers were so motivated by Lee’s actions, that they completely stopped what they were doing and turned off the machines, making the room silent for the first time in a long while. This is an iconic moment recreated for the film. Noise started up again when the city’s police chief arrived to arrest Lee. But she did not go quietly, “[s]he kicked, twisted, and screamed, and had to be stuffed into the squad car (Toplin, pp. 219).” This started a long fight for union recognition between the J.P. Stevens Company and their workers.

The Making of Norma Rae

Despite the conflict between J.P. Stevens and the mill workers fully sparked thanks in part to Lee, the factory still wasn’t willing to join the union. However, also thanks to Lee, the workers had outside media help who were willing to do anything they could in order to spread and represent union practices all over the world. Two of the most prominent figures to represent the message found in Lee’s story were film producers, Tamara Asseyeu, and Alex Rose. They both read about Lee’s story in a New York Times article in 1973. They knew it had potential to make an inspirational film. Both producers had their own approach to the story: Asseyeu wanted it to be socially conscious, and Rose wanted to make a “character-driven” story about “American subcultures” and the “human condition.” However, what made them compromise was their shared desire to spread the knowledge of union practices and Lee’s story (Toplin 222).

They wanted the story to have a strong woman lead and they had many actresses in mind to play Lee. These actresses were known for playing strong feminist icons during this time period. These actresses included Meryl Streep, Barbra Streisand, Bette Midler, Cicely Tyson, Diane Keaton, Jane Fonda, Vanessa Redgrave, Sissy Spacek, Shirly McLane and Anne Bancroft. However, due to scheduling conflicts and others turning down the role, none of these actresses accepted the role. While Asseyeu and Rose were disappointed that they couldn’t get any of the actresses they had in mind, they settled for then-unknown actress, Sally Field, as the lead character. This film would turn her into a household name and even allow her to win an Oscar for best leading actress. Choosing her would ultimately pay off for all three of these women (Toplin 217). Asseyeu and Rose wanted the real-life Crystal Lee as a consultant for the film. They would eventually offer her the position and she accepted. However, she would later leave production, and refused to let the filmmakers use the names of the people in her story, including her own. The only reason given to her departure is “creative differences (Toplin 223).”

By now, readers will notice that the film and main character are named Norma Rae, even though the film tells the story of a woman named Crystal Lee. As stated before, when Lee left the film’s production, she denied the access of the names of the real life figures in her story, including her own. As a result, one of the changes that had to be made was the name of the characters. This was one of the inevitable changes to the script due to behind the scenes issues. Other changes, such as changing a father-daughter relationship to a more romantic relationship between the two leads is not only unnecessary, but at the same time baffling. The story could have worked with a father-daughter relationship and may have been a more interesting relationship. However, the producers must have believed that audiences would find a romance more interesting.

When crafting a story, a writer often give insight into the main characters’ personal lives in order to explain their actions and personality as well the main conflict concerning the film’s community, otherwise the audience might not care if anything happens to the characters. Asseyeu and Rose wanted to handle Norma Rae the same way. They found it necessary to show the causes of Rae’s independence, aggressiveness, and her emergence as a union leader, while also staying true to southern women. Both producers decided to look to the research done by historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall in 1929. They found out that Hall’s examination of a strike at a Tennessee nylon plant had patterns of “disorderly women (Hall, 1929):” being young, single mothers out of wedlock who were sexually expressive.

This is evident in Norma Rae by her many earlier romantic relationships and her engaging in sexual activities for fun, and no further purpose. However, they made the character channel her rambunctious energy into integrating the workers’ union. Asseyeu and Rose wanted all women to do the same for their own causes. They were reminded of the importance of exposing the treatment of blue-collar workers by the film’s director, Martin Ritt. The reason why the two producers choose him to was due to his filmography about underdogs. Ritt only had one condition to directing the film and that was he got to bring in his own writing team, which they agreed. This allowed him to hire his best friends, allowing a comfortable working environment (Toplin 217).

Shortly after hiring Ritt, Asseyeu and Rose then had to find a studio willing to finance the film, knowing this would not be an easy task given the film’s pro union themes. Hollywood was never known for examining the issue of union organizations, with the exception of a few films such as the controversial Black Fury (1935), which has been banned in several U.S. states as inciting conflict, which should emphasize the fact that no studio was in a hurry to create Norma Rae. Studios such as Columbia Pictures, Warner Brothers, and United Artists rejected the project due to the subject matter and the amount of corruption found in unions during this time period. It wasn’t until they pitched their idea to 20th Century Fox, that they received the financing they needed. However, Fox was just as unsure about the project as other studios and was only willing to move forward when the production crew described the film as a “Female Rocky” (Toplin 217).

With financing taken care of, the team then had to find a textile mill in order to fit the setting of the film. The film being a pro-union movie was reason enough to convince companies to reject use of their mills. What didn’t help was the point that they would be interrupting regular operations at the factory. Asseyeu and Rose, wanting to still be as authentic to Crystal Lee’s story as possible, looked for a factory in North Carolina, to no avail. They ended up having to settle for a poor factory in Opelika, Alabama. However, this was lucky for both the production team and the factory since the team had to pay the factory 150’000 dollars in order to use it for filming, clearing some of the factory’s debt (Toplin 224).

Film’s Release and Legacy

Norma Rae was released on March 2, 1979, to worldwide acclaim, as well as 22 million dollars at the box office against a budget of 4.5 million dollars, all without crediting Crystal Lee. The film ended up teaching audiences about unions and exposing the treatment of blue-collar workers. This resulted in a backlash against the J.P. Stevens textile mill. One year after the film’s release, the company finally gave their workers union representations, after a lifetime of being anti-union, finally achieving Lee’s goal, thanks to this film. After this event, Crystal Lee decided to travel the world, promoting union practices while revealing that she was the “Female Rocky.” This has resulted in other businesses allowing union representation for their workers (Toplin 225).

Many authors have found the film and the history behind it so interesting that they feel it necessary to chronicle both Crystal Lee’s story and the film’s production. One of these authors is Robert Toplin. He dedicates an entire chapter to Norma Rae in his book History By Hollywood. He found the struggle between the mill workers and the J.P. Stevens Company to be very frustrating, finding the company to be irresponsible in making excuses to avoid unions. Toplin is unsure if the film had a real influence on the plant’s future integration within a union, he was happy for the workers, making it clear that Crystal Lee convinced him to take the side of the blue-collar workers. He also firmly believes in Hollywood’s emotional power to expose the southern mill to millions of Americans, as well as to publicize the unions’ cause more broadly than the previous decade of campaigning had done. Toplin believed that Norma Rae stimulated public awareness through cinematic realism, exposing the ugly working conditions of the factory. He also thinks that the film did a great job making a case for feminism as well and appreciated it being done subtly, just by having Rae be a leading figure in the union movement. If there were one criticism about the film that he had, it would have been that the film depicted Lee as alone in her fight against the factory. While this made her look more heroic, it neglects the contributions of the rest of her teammates. However, he still praised the film’s overall message (Toplin).

Theories

After reading the history behind this film from Toplin, Robert Nathan and many other scholars, a few theories have developed in my mind about this film, its production, and the true story behind it. As stated before, Crystal Lee left the production due to creative differences and my theory is because producers Tamara Asseyeu and Alex Rose had at one point been discriminated against for being women and Lee’s leadership is what they related to the most. This is why they wanted the adaptation to be centered on a feminist message. This may also explains why they were friends before the film entered production since they had the discrimination in common. The producers’ focus on a feminist story is most likely explanation as to why Crystal Lee left the production of the film, which is also theorized by Toplin and many other scholars. She wanted the film to stress the mistreatment of blue-collar workers instead of a feminist story, however, because Asseyeu and Rose were producers, they got the final say and all Lee could do was deny them the use of the names of the prominent figures in her journey. However, she was most likely proud of the film once it came out for being true to her struggles, which explains why she promoted herself as the real Norma Rae in travels promoting unions. This also explains why she did not seek legal action for using her story without her blessing, since she realized it could help in promoting unions. Another theory shared by Toplin, is the circumstances for the J.P. Stevens Company allowing union representation in their factories. This occurred a year after the film’s release when a new president of the company had just been appointed and he was the one who allowed such a change. I theorize that he was a fan of the film, which made him pro-union and wanted to correct what he felt was the previous owners’ mistakes.

Literature Review

Critics, such as Cathy Uccella, who brought a pre-conceived notion to reviewing Norma Rae; sometimes unions can be trouble. She felt this was a missed opportunity to explore the trouble unions can bring. She claimed that the film could have had more depth and meaning if they showed that this situation is not as black and white as the film presents it. Missed opportunities are one of the most brought up flaws about the film. Uccella further believed that the depiction of the factory was not problematic enough as well as finding the film “racist, poorly executing its aimed message and unnecessary changes to the story (Uccella, 1979).” For example, in the film, Nora and the union leader, Reuben Warshowsky, are presented as love interests, while in real life, Crystal Lee and Eli Zivkovich had a father daughter relationship. Uccella prefers the true story of Crystal Lee because she was affected by Lee’s cause and wants to support unions. While some of these changes occur in order to make the film more accessible to a wider range of audiences and fit the tone they were aiming for, what is most important was that Uccella was able to identify the importance of unions. I actually agree with some of Uccella’s points such as unnecessary changes and some of the problems of the factory being too subtle, but these are relatively minor complaints compared to the film’s message. However, I do not agree with her on the other issues in Lee’s life being completely absent. They were present, just not in the focus as much as other concepts.

Feminism was on both Asseyeu and Rose’s minds when making this film. As film producers; they knew how to do their jobs very well since their aimed release was during the second wave of feminism. This was when American society was becoming more receptive and fascinated by women’s issues during the 1970’s. Part of this movement included Congress introducing Title IX in the 1972 Education Amendment, which prohibited sex discrimination in the work place among many other things. Ritt also wanted to expose the mistreatment of blue-collar workers, as well as to promote unions and better treatment of workers. The production crew wanted the film to be a character driven story about a strong female protagonist who fights for what she believes in. This may also explain why the issues of the factory are not as touched on as much as much as Uccella stated it should be in her review of the film (Uccella, 1979). Lee wanted the film’s main message to be around equal rights for workers. Adaptations are a compromise, meaning changes will have to be made in order to create an engaging enough story, appropriate for the aimed tone and genre that can appeal to a wide audience, while at the same time fit the production crew’s vision. This is something Marcy Rein understood, whose positive review of the film caused Uccella to write her own review as a response.

Rein reviewed the film as its own separate entity with no biases and understanding that the flaws found within the film are the result of making a commercial film. “We are told little directly about conditions at the mill—this isn’t a documentary—but we’re shown enough.” (Rein, 1979). Since this film has a narrative, it is impossible to cover every single detail going on during this event. Rein also understands the filmmakers’ focus on the personal journey of a young woman’s struggle to overcome her corrupt employers, not necessarily to document the drama within every person in the factory, but the audience witnesses the struggles of each character through Rae’s perspective. Rein is still fair to the film, criticizing the pacing and trying to simplify the conflict, but still moves on to compliment the rest of the film, such as the production design and writing (Rein, 1979).

As stated before, Cathy Uccella wrote her review of the film as a response to Marcy Rein, which is a risky practice. When a critic writes his/her own review in response to someone else, they can either be seen as very bold, correcting them to look for the deeper meaning and make sense of a story, or can make them look very foolish, telling the other critic that their interpretation is wrong. Uccella appears more bold since she is subtly reminding Rein that one can easily learn the film’s message from reading Crystal Lee’s story and is disappointed that some of the more interesting aspects were overlooked, but is professional enough to not insult or seem disrespectful to Rein. Uccella is right that this film has the potential to disrespect Crystal Lee and her struggles by not representing them as accurately as possible, since her story deserves respect and would have been better with her involvement. Rein, meanwhile seems to understand Asseyeu and Rose’s perspective in her review of the film. Rein knew that these producers wanted to show the hard work put in by their strong feminist hero in order to ensure that her family, friends and neighbors were treated equally to their employers. Rein thought it would be more organized to follow this individual since the audience can realize that she is just like them. It might affect the pacing negatively by focusing on too many characters.

Personal Interpretations of the Norma Rae and Crystal Lee’s Story

There are many ways one can interpret both these stories. Audiences either like the original story and don’t like the adaptation, or they don’t care about the original story and only seek to be entertained by the adaptation. It is very rare that one sees someone that likes both the true story and its less faithful adaptation, however, I am one of those people. I am able to enjoy both the true story of Crystal Lee and the more fictionalized Norma Rae, but in very different ways.

The story of Crystal Lee is very interesting to read about. Lee was so strong, selfless and heroic. I find Lee’s rebellious behavior fascinating. In the story, she was willing to describe her relationship with Eli Zivkovich as a father-daughter relationship, despite her real father still being alive during this time. You also feel bad for her struggles to have the mill integrated within the union, only for the film adaptation to ironically cause the J.P. Stevens Company to give in and give their workers union representation.

I enjoy the film as its own separate product since it still has the message of fighting for what you believe in, no matter the odds. I judge it as a film, not a biography. For example, towards the end of the film, I would have liked to see Rae go quietly with the police, smiling, knowing that she inspired her coworkers, instead of kicking and screaming like Lee. Yes, the final ending is true to Lee’s story, but I feel that would have symbolized that her character development was complete, leaving a satisfying feeling to the audience. When the union organizers arrived in Rae’s town, she was hesitant to support them. Even when she was helping them, she was still unsure of their cause, but by the end of the film she had the full confidence to do something as brave as protesting the factory and promoting the union during work hours. What I find most enjoyable about the film is that it manages to contain a coherent story, yet still come across as a slice of life story, showing Rae’s life interacting with her family and neighbors and thus giving the audience insight on to how much the factory is affecting them. However, the film is not perfect, and its flaws do come primarily as a consequence of adapting someone else’s story into a Hollywood film. For example, the pacing is so fast that it feels like the events of the film are taking place over the span of a few days instead of more realistic months. I also firmly believe that Norma Rae and the union worker’s romance was not necessary. They could have hired an older actor and portrayed the more interesting father-daughter relationship. However, these complaints are mostly nitpicks, and like Marcy Rein, I can appreciate that they are still staying true to Crystal Lee’s story, even if their main priority is to make a satisfying film.

Conclusion

Crystal Lee’s story and its film adaptation, Norma Rae, are very important stories for students and employees to learn about. Both tell of a struggle to unionize a corrupted factory, which only integrated later on after the film exposed them. While many may argue that the film is not faithful enough to the true story, it should ultimately not matter because both the true story and the film can teach audiences about unions and how they benefit workers and companies. If companies such as Uber, Sega, and various school districts learn from this film, it could help their workers be happy and potentially boost their productivity.

Works Cited

Toplin, RB. 2010, History by Hollywood: The Use and Abuse of the American Past

Ritt, M. 1979, Norma Rae

Toplin, RB. “NORMA RAE: Unionism in an Age of Feminism.” Labor History, vol. 36, no. 2, Spring 1995, pp. 282–298.

Nathan, Robert, and Jo-Ann Mort “Remembering Norma Rae.” Nation, vol. 284, no. 10, Mar. 2007, pp. 16–20

Taylor, Vicki Fairbanks, and Michael J. Provitera. “Teaching Labor Relations with Norma Rae.” Journal of Management Education, vol. 35, no. 5, Oct. 2011, pp. 749–766,

“A Gift from ‘Norma Rae.’” The Chronicle of Higher Education, no. 2, 2007.

Uccella, Cathy. “’Norma Rae’ Sellout.” Off Our Backs, vol. 9, no. 7, 1979, pp. 29–29.

Rein, Marcy. Off Our Backs, vol. 9, no. 4, 1979, pp. 23.

Zieger, Gay P., and Robert H. Zieger. “Unions on the Silver Screen.” Labor History, vol. 23, no. 1, Winter 1982, p. 67.

Kennedy, Ann. “‘Finding Your Way When Lost’: Class and the American Girl.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 34, Jan. 2018, pp. 53–60.

Martin, Judith. “Norma Rae: Good old Good vs. Evil” Washington Post, 1979.

Comments