“A sensual, scholarly, magic-realist exploration of Black history and Black desire.“

-The New York Times

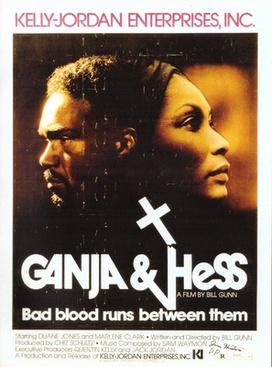

Ganja & Hess is a 1973 experimental horror film, written and directed by the visionary auteur Bill Gunn. It emerged during the Blaxploitation and Black Horror wave that swept the 1970s. According to renowned film scholars Manthia Diawara and Phyllis Klotman, in Ganja and Hess: Vampires, Sex, and Addictions, the film’s producers originally intended for it to be a straightforward blaxploitation film – a literal “Black version of white vampire films” (299). However, Bill Gunn had far grander ambitions. He meticulously crafted the narratively complex Ganja & Hess. Gunn’s horror masterpiece exerts an irresistible pull on the viewer, demanding that they bring their own interpretations to the fore, as the film brims with rich and competing imagery and narratives vying for ultimate authority.

Summarizing Ganja & Hess proves challenging due to its deliberate departure from conventional storytelling norms. In this film, you won’t find a clear-cut hero or a character whose narrative is given particular weight or compassion. There’s no discernible cause-and-effect structure, no traditional beginning, middle, or end. Instead, the film unfolds as a series of juxtaposed images, storylines, themes, and characters, all vying for entry into the viewer’s psyche.

Superficially, the film explores Dr. Hess Green and his intricate relationships. Dr. Green is portrayed by Duane Jones of Night of the Living Dead fame. There is the dynamic between him and his assistant, George Meda (played by director Bill Gunn), which unfolds as a clash between an artist and a capitalist that Meda ultimately loses. His narrative turns tragic when he becomes a victim of Hess’ vampirism. Hess’ connection with Ganja (Marlene Clark) is also a central element of the story. Initially introduced as Meda’s wife, she later becomes Hess’ wife following Meda’s untimely demise. Ganja embodies the modern Black woman who has grown weary of respectability politics and misogynoir. She is initially horrified to learn of what happened to her missing husband, but interestingly enough, she decides to join Hess and the two eventually marry. Gunn leaves viewers to contemplate if this is agency or betrayal. Lastly, we have Hess’ chauffeur, Rev. Luther Williams (Sam Waymon), who moonlights as a part-time minister.

Delving beneath the surface, the film presents itself as a narrative with three distinct voices in competition, accompanied by a multitude of juxtapositions that beckon the viewer to engage with it on multiple layers. It provides the origins of Dr. Hess Green’s vampirism in a documentary-style exposition, in which the minister explains that Green’s bloodlust is rooted in an ancient African dagger tainted with blood. However, it refrains from showcasing a clear beginning, offering instead various snapshots of the present.

The evolving relationship between Ganja and Hess is portrayed in its gradual development but isn’t depicted as the sole focal point of the film. Even Hess’s death, preluded by his penitence in the shadow of his chauffeur-minister’s church, appears as merely an unceremonious exit from the unconventional narrative, with Ganja assuming a more central role. The minister invites us to view Hess as a victim of his own bloodlust, akin to his actual victims (Diawara, Klotman 301). Ganja can be seen as a heroine, representing a contemporary Black woman tired of subservience to both the church and Black men. She might be content that Meda and Hess, the self-destructive artist and the bourgeois patriarch, have exited the stage (Diawara, Klotman 313). Conversely, some viewers may perceive her as a monster who, unlike Hess, refuses to repent and takes his place, perpetuating the bloodlust. Ganja watches coyly from a window as the man that she and Hess fed on earlier in the film emerges from the lake and sprints toward her. She welcomes him as her vampiric dinner guest and implied lover.

Whose narrative authority should we accept? Should it be the minister, who asserts that Hess’s sin lies in turning away from Christ (Diawara, Klotman 311)? Or perhaps George Meda’s philosophical reflections on Black Death as an art form, a necessary catalyst for the emergence of a better follow-up generation (Diawara, Klotman 311)? Alternatively, should we follow Ganja on her path to Black woman liberation (Diawara, Klotman 313)? Gunn leaves the viewer to contemplate these questions, offering no definitive answers.

Ganja & Hess serves as Bill Gunn’s personal playground, where he plays with the idea of final narrative authority and explores the complex terrain of Black identities in the African Diaspora within a nonlinear timeline. The outcome is a beloved hidden gem in the annals of horror film history. Gunn achieved this critical acclaim by taking familiar vampire tropes and injecting fresh life into them through unconventional narrative techniques and themes drawn from Black literature. It is a critical darling that was nevertheless suppressed for not being the cash grab the studio intended it to be, and saw its auteur remove his name from subsequent sexploitation cuts of the film (Diawara, Klotman 300). There are cuts of the film where full male nudity is presented in a sexually suggestive manner that some have suggested was a ploy to make the movie sell through infamy. Luckily, an original print remains, and audiences are allowed to experience Bill Gunn’s horror masterpiece. Film critic James Monaco said it best, positing that the film is “the great underground classic of Black film, and… the most complicated, intriguing, subtle, sophisticated, and passionate Black film of the seventies” (299).

Works Referenced

Diawara, M., Klotman, P. “Ganja and Hess: Vampires, Sex, and Addictions.” Black American Literature Forum 25(2): pages 299-314.

Bill Gunn. Ganja & Hess starring Duane Jones, Marlene Clark, Bill Gunn, and Sam Waymon, Kelly-Jordan Enterprises, 1973.

Eggert, Brian. “Ganja & Hess.” Deep Focus Review. Accessed at https://deepfocusreview.com/definitives/ganja-hess/

Comments