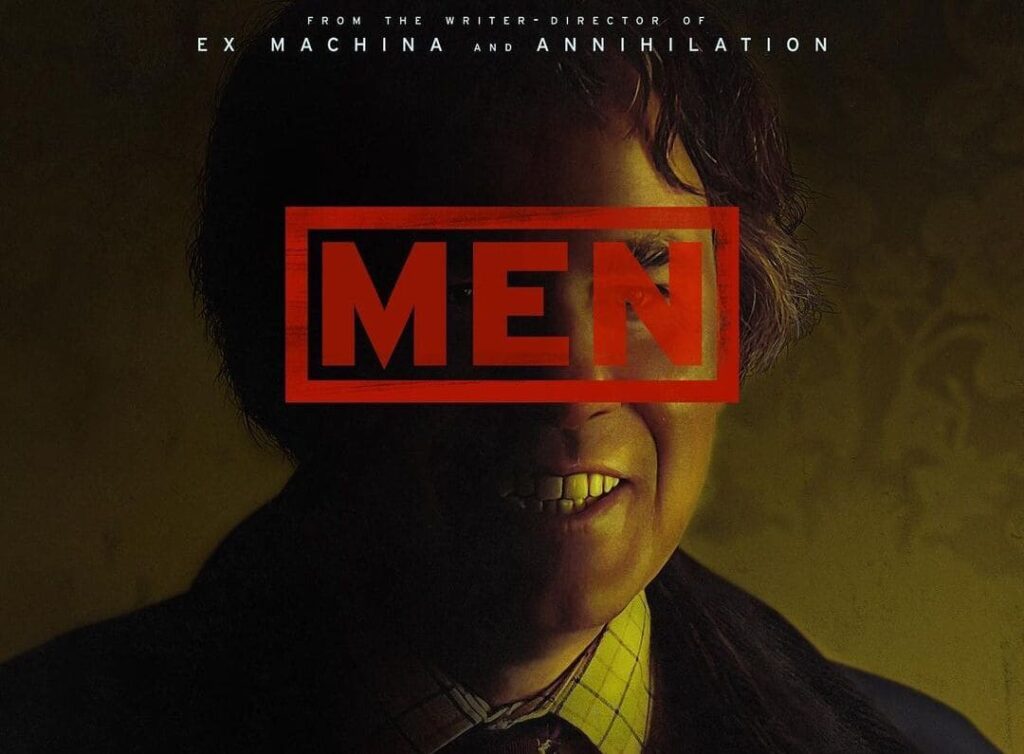

Another addition to a wave of horror films whose premise lies in a simple fear, “imagine being a woman,” Men feels rather hollow in the horrors presented. Alex Garland’s latest feature focuses on recent widow Harper Marlowe’s (Jessie Buckley) solo-trip to the countryside that is disrupted by the men she meets during her stay, all played by Rory Kinnear. Despite being visually visceral (truly consider not eating before you watch this), the message behind all the gore remains incomplete. I left the theater feeling like something, many things, were still missing from the story.

The brief initial metaphor of Harper as Eve sets the narrative up as an examination of women being punished for not meeting the, at times absurd, expectations of men. As such, every man Harper comes across demands something of her and retaliates when their wants are left unmet. The vicar wants Harper to be innocent; the policeman wants her to be grateful; the little boy wants her to play with him; Geoffrey, the AirBNB host, wants her to be dependent and meek; James (Paapa Essiedu), her recently deceased husband, wants her to be unconditional in her forgiveness and love. However, the devices meant to carry this thread of demand and retribution are weakly developed. Harper’s singing in the tunnel, for example, serves as nothing more than a means to awaken a man who chases Harper through the film. Despite the recurring tunnel tune, the Green Man’s wants are left undefined and what her solitary pleasure invokes in him is left unexplored.

The men of the village in general are immediately ravenous for her attention, almost comically so. The insidiousness of their requests is dampened by how borderline ridiculous their reactions are. Likewise, the men of the village sharing the same face, which can be read as misogyny being ubiquitous and similar across men, loses impact given most of these men are shallow, violent caricatures. It’s a bit ironic that the titular characters are the most disappointing aspect in a feature examining misogyny. Geoffrey and James are the best written men given their harm is layered. They are not immediately threatening but rather gain Harper’s trust before the potential for their betrayal becomes apparent. However, the film spends more time terrorizing the main character with recurring visits from the Green Man and unwanted advances from the vicar.

As for Harper, our tortured protagonist at times is more of a prop in her own story than the main participant. Harper was passive to a fault in a plot that simultaneously showed her as someone willing to act. Her reaction to more explicit acts of violence (James punching her, the vicar’s comments about her virginity, and the policeman’s apathy towards her fear are all immediately met with anger) clashes with her deer in headlights behavior. There was a potential to explore the differences in fight, flight, or freeze responses, especially if hesitation was woven into Harper’s character. Instead, certain moments, such as her accepting the arm of the Green Man when he reaches out for her, feel as if she’s been zapped of all characterization in favor of moving the plot forward.

The most glaring example of her passivity is the lack of an obstacle for the first two thirds of the movie. There’s nothing physically keeping Harper in the village. Yet, despite the increasingly uncomfortable getaway, she sticks around. The encouragement from Riley (Gayle Rankin) to take up space because she deserves to feels more like a satirical interpretation of how women talk to each other, not to mention a weak reason for Harper to stay in the story, than sound advice from someone’s best friend.

For some, the visual oddities and excess gore will resonate a deeper message. For me, I fear examining how deeply ingrained misogyny can be through mostly exaggerated manifestations can have the opposite effect on viewers. Instead of leaving the theater questioning our individual participation in or reinforcement of misogyny, viewers may leave more pressed to understand why the birthing sequence at the end was so bloody long.

Comments