Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror moves chronologically through Black representation in horror films, as told and viewed by Black filmmakers and actors in this genre. I think it is important that the perspective is given solely to Black actors and filmmakers and is not counterpointed or discussed with White people. This film is about the Black experience as it relates to Black horror films. This is important for two reasons — #1 It will give non-Black viewers some perspective on the Black experience in representation or lack thereof; #2 As mentioned by Rachel True (actor in The Craft), sometimes the racism is so normalized in America (even to people of color) that its presence is often ignored. We all need to acknowledge the history of representation so positive change occurs.

Because of laziness, I will be abbreviating Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror as HN:HBH.

Why Horror?

First, horror movies are profitable. Beyond that, a common theme throughout the horror genre, as articulated in many interviews in HN:HBH, is that Black history is Black horror. This message is weaved through the film and through the genre. The phases of Black representation in horror relate directly to the political and social climate of the time. As you will see in the timeline below, the first film mentioned, Birth of a Nation, is not a typical horror film. To Black viewers, however, it definitely reads as horror. The heroes in this film are the KKK! Birth of a Nation was screened at the White House and ENDORSED BY THE PRESIDENT! That doesn’t seem as shocking today as it might have seemed ten years ago, but still unacceptable. What message must have that sent to Black Americans? The only representation of Black people in films was meant to incite fear and demonize Black people.

As you watch any film, especially horror movies this Halloween, keep an eye out to see if Black characters are fully developed, or do they fall into one or more of the tropes discussed in HN:HBH (and listed below).

Black Tropes in Horror Movies (and most other genres)

- Magical Negro/Uncle Remus

- Sacrificial Negro

- Faithful Servant

- Voodoo/Tribal

- Comedic Buffoon

- First to Die (see Skat Man in The Shining)

- Token (again, see Skat Man in The Shining)

Timeline of Black Horror

1915: Birth of a Nation

1920s-1930s: White people playing Black people (not positively)

1940s: Some positive changes? Except for the “based on a true story” claim in demonizing films.

1940: Son of Ingagi — First representation of a Black woman in STEM; First major horror film with an all-Black cast.

1950s-1960s: Almost no Black people to be found; Creatures/Monsters are modeled to look like non-whites, a stand-in for the missing Black actors.

1968: Night of the Living Dead — Black protagonist as protector/destroyer, not victim/villain; Angry White “mob” kills Black protagonist.

1970s: Blaxploitation; Tricky representation/profiling; Prominent fear of Black women’s sexuality

1972: Blacula — Strong Black protagonist; Black director; White crew

1973: Scream Blacula Scream — Black female lead; Voodoo represented as a history, not a terrifying magic

1973: Ganja and Hess — Black filmmaker; Represented Black fear of police even from a wealthy, educated Black man; Standing ovation and top award at Cannes Film Festival; Unreleased in America but available at the Museum of Modern Art

1974: Sugar Hill — Black men lust for White women trope; Strong, smart Black female protagonist

1980s — Horror stayed in the White suburbs; Blacks were dangerous/criminals

1990s — More Black women in film in general; Hip-Hop shows up in horror

1991: The People Under the Stairs — Black fear of White space

1992: Candyman — Dealt with racism/race issues; Black boogeyman obsessed with White woman; White writers; Sequels provide backstory and context making the original more meaningful

1995: Tales from the Hood — Tackled issues like abuse, gang violence, racism, police brutality; Gave justice and redemption to people of color that they were not getting in real life.

1995: Tales from the Crypt: Demon Knight — Black female protagonist is finally the “final girl”

1997: Eve’s Bayou — Representation of a Black experience in the South with a Black, young, female protagonist

2000s: Self-reflexive horror films; Exposure of tropes (usually for comedic purposes); Former focal point of fear evolves into heroic characters

2017: Get Out — Pressure valve release for political climate; Similar to Night of the Living Dead, but with a happier ending

Conclusion

What’s next? As Jordan Peele says in the film, “White people will see movies with non-white people. You just have to make them.” The horror genre reflects the role of Black people in all film and the perception of the Black population by White America. It is getting better, and more opportunities are coming for Black filmmakers. Let’s hope this momentum continues.

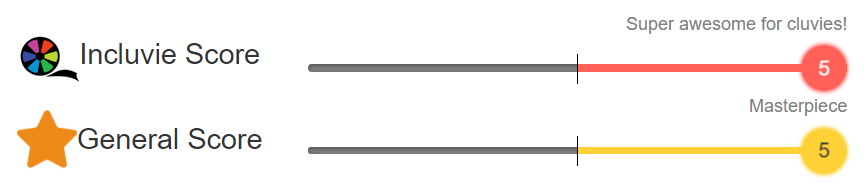

Incluvie Score: Black contributors (actors and filmmakers); Black filmmaker

General Score: Extremely well-done documentary; Important to record a history that is often ignored and neglected

(This article was originally published by Sarah Erskine on Medium.)

Comments