When her mother Edna (Robyn Nevin) goes missing, Kay (Emily Mortimer) and her adult daughter Sam (Bella Heathecote) take a trip out to Kay’s childhood home to look for her. While in the house, Kay notices things out of place: rotten fruit, a chair facing the wrong way. More than that, a sense of general wrongness slowly steals over Kay and Sam. There are noises in the walls and shadows under the doors. Post-Its are found around the house with handwritten notes as harmless as “Turn Off Faucet” and as creepy as “Don’t Follow It.”

Edna returns, but that’s not nearly the end of the story. She won’t say where she’s been and there’s an unexplained black bruise on her chest. Kay and Sam can’t agree on how best to take care of Edna, with Kay considering an assisted living facility in Melbourne and Sam offering to move in with her grandmother. Yet as Edna descends further and further into her dementia, the house around the three women rots and decays with increasing frequency. Kay literally fights for her mother’s sanity while Sam gets trapped by the house in a moldy and decrepit crawl space. Is Edna’s dementia connected to the house? If so, what does that mean for Kay and Sam?

Relic is a film that depends on darkness, the unknown, and foreboding to create an atmospheric sense of dread that’s done to perfection. Rarely does a horror movie set aside the predictable jump scares and grotesque monsters with the success that Relic manages to pull off. Instead, the horror of Relic lies in shadows, in hints of creatures moving under the bed, in strange noises coming from inside the walls. Edna’s forgetfulness and paranoia add a level of uncanny foreboding that lends a sense of dread to even her most innocent comments and actions. She gives her granddaughter her old wedding band, only to later accuse Sam of stealing it and violently ripping it from Sam’s finger. This action, while a sad one signaling Edna’s loss of mental health, also becomes sinister within the framework of the movie’s already eerie atmosphere. Sam now has a bruise on her finger, not unlike the bruise growing over Edna’s chest.

Most of the film is shot in darkness with faded colors. This choice not only indicates Edna’s mental state fading into darkness, but it adds a veil of claustrophobia to Relic that mimics Kay and Sam’s feeling of being trapped: first by their familial duty to Edna, then by the house itself, and finally by the vision of their own futures laid out before them.

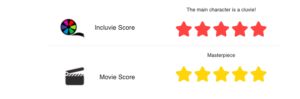

Relic’s three stars are all women, with men taking very minor roles for the film; it passes the Bechdel Test by default. Aside from Edna longing for her dead husband for a couple of small moments, men barely factor into the movie at all. Feminine energy radiates out of the film through Sam’s compassion, Kay’s care, and Edna’s fighting spirit. Rather than detaching them from each other, the shared sense of duty and connection bring them closer. Any resentment they feel is drowned out by a desire to do right by each other.

Older women don’t generally fare well in movies, books, and other media. They are shrews, spinsters, hags, or witches. They prey on the young to maintain youth and beauty. They cast spells, eat children, make life hell for everyone around them by insisting on having their way. Old women, even more than old men, get treated like a burden on society. Once they are past child-bearing age and youthful attractiveness, why can’t they just go away?

While it would be easy to pigeonhole Edna into the category of “hag,” Relic gently (and sometimes not gently) guide her on a journey that ends with compassion: for her, from her. She and Sam had/have a close relationship, as Sam finds her grandmother’s sweater, inhales her scent, and wraps it around herself for comfort. Edna is not the villain; she’s as much a victim of what’s happening to her as Kay and Sam are.

Few movies deal with aging (particularly aging women) with as much compassion as Relic does. Yet it’s not sickly sweet and not a soapbox rant against ageism. Relic simply is, allowing the horror to seep in quietly and carefully. As with other quiet horror films such as The Babadook (also from Australia, and also directed by a woman), Relic shows us that sometimes the worst monsters are the ones that come from within — the ones we are powerless to stop.

Comments